Download complete book as HTML ZIP-File

Download the E-Book: Someone has poisoned me

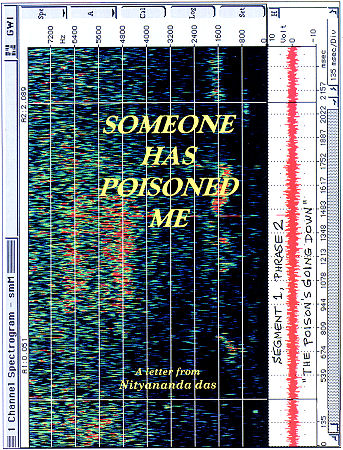

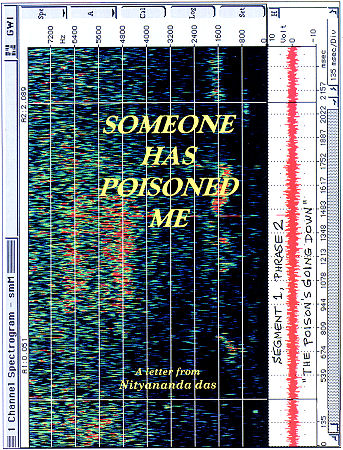

Someone Has Poisoned Me - BY: NITYANANDA DAS

Download complete book as HTML ZIP-File

Download the E-Book: Someone has poisoned me

The Facts About Srila Prabhupada's Poisoning by Arsenic

"So as Krishna was attempted to be killed... And Lord Jesus Christ was killed.

So they may kill me also." (Srila Prabhupada, May 3, l976, Honolulu)

"my only request is , that at the last stage don't torture me, and put me to death"

(from SPC Vol. 36, November 3, 1977 tape recorded Room Conversation)

[PLEASE NOTE: ADDRESSES, EMAILS, PHONE NUMBERS ETC. MIGHT NO LONGER BE CORRECT!]

I am an evil, poisonous smoke…

But when from poison I am freed,

Through art and sleight of hand,

Then can I cure both man and beast.

From dire disease ofttimes direct them:

But prepare me correctly, and take great care

That you faithfully keep watchful guard over me:

For else I am poison, and poison remain.

That pierces the heart of many a one.

(Valentini, 1694)

Come bitter pilot, now at once run on

The dashing rocks thy seasick weary bark!

Here's to my love! O true apothecary!

Thy drugs are quick. Thus with a kiss I die.

(Romeo and Juliet, act 5, sc. 3)

Toxicology dates to earliest man, who used animal venoms and plant extracts for hunting, waging war, and assassinations. The Ebers papyrus (circa 1500 B.C.) contains information pertaining to many recognized poisons: hemlock (the state poison of the Greeks); aconite (a Chinese arrow poison); opium (used as both poison and antidote); and such metals as lead, copper, and antimony. There is also an indication that plants containing substances akin to digitalis and belladonna alkaloids were known. Hippocrates (circa 400 B.C.) documented a number of poisons and clinical toxicology principles pertaining to bioavailability in therapy and over-dosage.

In the literature of ancient Greece, there are several references to poisons and their use. Theophrastus (370-286 B.C.) a student of Aristotle, included numerous references to poisonous plants in De Historia Plantarum. Dioscorides, a Greek physician in Emperor Nero's court, produced the first classification of poisons, which was accompanied by descriptions and drawings. His separation into plant, animal, and mineral poisons not only remained a standard for 16 centuries but is still a convenient classification today. Dioscorides also dabbled in therapy, recognizing the use of emetics in poisoning and the use of caustic agents or cupping glasses in snakebite.

Poisoning with plant and animal toxins was quite common. Perhaps the best-known recipient of a poison used as a state method of execution was Socrates (470-399 B.C.). Expeditious suicide on a voluntary basis also made use of toxicologic knowledge. Demosthenes (385-322 B.C.), who took poison hidden in his pen, was only one of many examples. The mode of suicide calling for one to fall on his sword, although manly and noble, carried little appeal. Cleopatra's (69-30 B.C.) knowledge of natural, primitive toxicology permitted her the more genteel method of falling on her asp instead.

The Romans, too, made considerable use of poisons in politics. One legend tells of King Mithridates VI of Pontus whose numerous acute toxicity experiments on unfortunate criminals led to his eventual claim that he had discovered "an antidote for every venomous reptile and every poisonous substance." He himself was so fearful of poisons that he regularly ingested a mixture of 36 ingredients as protection against assassination. The poetic treatise "Theriaca" by Nicander of Colophon (204-135 B.C.), dealt with poisonous animals; his poem "Alexipharmaca" was about antidotes.

Poisonings in Rome took on epidemic proportions during the fourth century B.C. (Livy). It was during this period that a conspiracy of women was uncovered to remove the men from whose death they might profit. Similar large-scale poisoning continued until Sull issued the Lex Cornelia (circa 82 B.C.). This appears to be the first law against poisoning, and it later became a regulatory statute directed at careless dispensers of drugs.

Prior to the Renaissance, the writings of Maimonides (Moses ben Maimon, A.D. 1135-1204) presented a treatise on treatment of poisonings from insects, snakes, and mad dogs (Poisons and Their Antidotes, 1198). From the early Renaissance, the Italians, with characteristic pragmatism, brought the art of poisoning to its zenith. The poisoner became an integral part of the political scene. The records of the city councils of Florence, and particularly the infamous Council of Ten of Venice, contain ample testimony of the political use of poisons. Victims were named, prices set, and contracts recorded, and when the deed was accomplished, payment were made.

An infamous figure of the time was a lady named Toffana, who peddled specially prepared arsenic-containing cosmetics (Agua Toffana). Accompanying the product were appropriate instructions for use. Toffana was succeeded by an imitator with organizational genius, a certain Hieronyma Spara. A local club was formed of young, wealthy, married women, which soon became a club of eligible young, wealthy widows, reminiscent of the matronly conspiracy of Rome centuries earlier.

Among the prominent families engaged in poisoning, the Borgias are the most notorious. Alexander VI, his son Cesare, and Lucretia Borgia were quite active. The deft applications of poisons to men of stature in the Church swelled the holdings of the Papacy, which was the prime heir.

A paragon of the distaff set of the period was Catherine de Medici. She exported her skills from Italy to France, where the prime targets of the ladies were their husbands. Under guise of delivering provender to the sick and the poor, Catherine tested toxic concoctions, carefully noting the results.

Culmination of the practice in France is represented by the commercialization of the service by Catherine Deshayes, who earned the title La Voisine. Her business was dissolved by her execution. Her trial was one of the most famous of those held by the Chambre Ardente, a special judicial commission established by Louis XIV. La Voisine was convicted of many poisonings, including over 2000 infants among the victims.

The tradition of the poisoners spread throughout Europe, and their deeds played a major role in the distribution of political power through the Middle Ages. Pharmacology, as we know it today, had its beginning during the Middle Ages and early Renaissance. Concurrently, the study of the toxicity and the dose-response relationship for therapeutic agents was commencing (Paracelsus, 1493-1541).

Orfila, a Spanish physician in the French court, was the first toxicologist to use autopsy material and chemical analysis systematically as legal proof of poisonings. His introduction of this detailed type analysis survives today as the underpinning of forensic toxicology. Magendie, a physician and experimental physiologist, studied the mechanisms of action of emetine, strychnine, and "arrow poisons". His research into the absorption and distribution of these compounds in the body remains a classic in toxicology and pharmacology. (Casarett and Doull's Toxicology)

The alchemist's symbol for arsenic, a menacing coiled serpent, probably symbolizes very well the element's prevailing evil reputation. Anxiety about arsenic is not difficult to comprehend, inasmuch as arsenic compounds were the preferred homicidal and suicidal agents during the Middle Ages and arsenicals have been regarded largely in terms of their poisonous characteristics in the nonscientific literature. For example, an almost clinical description of acute arsenic poisoning appears in the novel Madame Bovary. Flaubert's extensive account of Emma Bovary's prolonged death throes must have made a vivid impression on many a reader. Arsenic has also been referred to in more recent literature, such as Kesselring's drama, Arsenic and Old Lace. Although arsenic was only one of three poisons used by the Brewster sisters to dispatch their guests, "Strychnine and Old Lace" or "Cyanide and Old Lace" would not have had as great an impact on the public.

Arsenic had widespread use in eighteenth-and nineteenth-century medicine as a tonic, or "alterative." At about the same time that Flaubert was writing Madame Bovary, there were a half-dozen "official" arsenicals listed in the U.S. Dispensatory. The prevailing professional opinion at that time concerning the medicinal use of arsenic was summarized as follows: "Arsenic is a safe medicine; none of the respondants having found it permanently detrimental…" …The heyday of arsenical chemotherapeutics occurred in the early part of the twentieth century, when Ehrlich discovered Salvarsan (arsphenamine), which was effective in treating human venereal disease; but the use of these compounds declined after World War II, with the advent of the more specific antibiotics.

The earlier medicinal uses and criminal abuses of arsenicals provide a helpful background of information about these compounds. (Arsenic, 1977)

Srila Prabhupada left this mortal world on November 14, 1977.

But He lives forever in His instructions, and His followers will always live with Him.

"He reasons ill who tells that Vaishnavas die

While thou art living still in sound!

The Vaishnavas die to live, and living try

To spread the Holy Name around"

(Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Thākura)

HARE KṚṢṆA HARE KṚṢṆA KṚṢṆA KṚṢṆA HARE HARE

HARE RĀMA HARE RĀMA RĀMA RĀMA HARE HARE